For about one hundred years secular scientists have been noting the unique traits and adaptations of the woodpecker. [For example, see Burt, W.H., “Adaptive Modifications in the Woodpecker,” University of California Publications in Zoology, 32(1930): 455-524.] For several decades now creationists have been interpreting these traits and adaptations as evidence for the woodpecker as an engineered-by-God lifeform. In the 1990 book The Amazing Story of Creation from Science and the Bible (pp. 101-103) by ICR scientist Duane Gish, several seemingly engineered characteristics are listed. These are the woodpecker’s bill, feet, tailfeathers, head, and tongue. In the present article I am going to look a little deeper into these engineered features of the woodpecker. Along with describing the features I will attempt to determine the logical feasibility of them being just adaptations from another bird kind instead of being made in the beginning by the Creator with these marvelous features. Of course I will use biblical presuppositions that undergird my Christian worldview.

Figure 1. Ivory-Billed Woodpecker

The first thing to make clear is exactly what is a woodpecker. This is needed because there are some non-woodpecker birds that have some of the characteristics of true woodpeckers. Perusing secular woodpecker literature in order to answer the question can be confusing due to its reliance on evolutionary thinking. All true woodpeckers are hole-nesters with the ability to excavate their own living spaces. They do this excavation in trees or tree substitutes like columnar cacti or wooden telephone and utility poles. In the Picidae family (picids) are three sub-families: the Jynginae or wrynecks; the Picumninae or piculets; and the Picinae, also known as the true woodpeckers. I will be mainly discussing the true woodpeckers. So, I will put no emphasis on the discussion of wrynecks or piculets.

Here are the six distinctive morphological features of the true woodpecker from the secular literatures: 1-a long, stiff tail for bracing against tree trunks, 2-short legs and long toes to assist in climbing vertical surfaces like tree trunks, 3-a head engineered to withstand repeated hammering against hard surfaces, 4-a long, straight bill designed for chopping into wood, removing bark or probing into crevices, 5-a long, extensible tongue with a barbed end, able to reach deep into narrow openings and extract hidden insects, and 6-nostrils covered with appropriate feathers to keep them free of wood chips. There are 24 genera of true woodpeckers (Picinae) that have been identified worldwide and that have the above six morphological features.

There is one genus of true woodpeckers, the Campephilus, that comprises a group of birds with outstandingly crested heads and predominately black backs. These large woodpeckers have long, straight, chisel-tipped bills and long, stiff tails that allow them to demonstrate impressive bark-stripping and wood excavating capabilities. These abilities permit them to gain easy access to the hefty beetle larvae that are their primary food source. Within the Campephilus genus are three North American species consisting of the pale-billed woodpecker, the imperial woodpecker, and the ivory-billed woodpecker. The latter two are endangered, the imperial may even be extinct.

Next, let’s look at each of the six engineered features in some more detail.

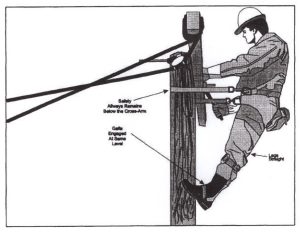

Woodpecker’s Tail: The woodpecker tail is designed to help resist the force of gravity and allow the bird to work with ease on vertical tree surfaces. There are two forces that the bird must account for, an outward force tending to pull it away from the tree, and a stronger downward force. These must be resisted by the combined actions of the tail and feet. In Figure 2 is the familiar situation of the utility worker on a pole which demonstrates the exact same situation that the woodpecker must handle where the worker’s boot spikes and legs are analogous to the woodpecker’s stiff tail, and the worker’s waist strap is analogous to the woodpecker’s clawed feet. This is basic mechanical engineering.

Figure 2. Resisting the Forces

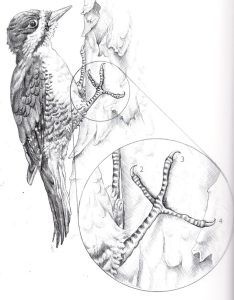

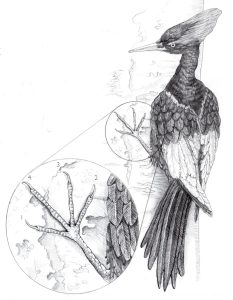

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the mechanical design of the woodpecker tail & feet in more detail.

Figure 3. Woodpecker Tail with Stiff Pointed Central Feathers.

Figure 4. Mechanics Demonstration of Tail, Feet, and Claws.

Another amazing aspect of the tail design of the woodpecker is the order of tail feather replacement during molting. In other bird species the most common tail molt pattern is from the middle outward. For the woodpecker this order would be very disruptive to the ability of the woodpecker to attach itself to a tree. So, in the woodpecker the tail molt begins with the second-innermost pair of feathers and proceeds outward. The critical central pair of stiff feathers is replaced last and only after the newly regenerated feathers on either side of the central ones are big enough to temporarily serve to support the bird while at a tree.

With the woodpecker the central tail feathers are black due to granular pigments called melanins that make the feathers more resistant to wear.

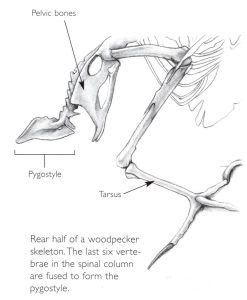

In Figure 5 is shown the skeletal construction of the back end of the woodpecker. The tail feathers and the muscles that move them are attached to the pygostyle; a bone formed by a fusion of vertebrae in the bird’s spinal column. Woodpeckers have an enlarged construction of bone and muscles in this area compared to other birds that is required in order to allow for their need to hang onto the side of trees. To the open-minded person all of these tail morphological features indicate intelligent design, not evolution.

Figure 5. Reinforced Woodpecker Skeleton for Tail.

Woodpecker’s Legs, Toes & Claws: Figure 6 shows some of the common avian toe arrangements. The zygodactyl arrangement is generally ascribed to woodpeckers as seen in the figure. In these configurations toe number one (think of it as the human big toe) is called the hallux; in some bird species it is absent. The anisodactyl feet of crows and other perching birds have backward-pointing hallux, with the other toes #2-3-4 all pointing forward. The term zygodactyl comes from the Greek words for yoke and finger and refers to a yoke-like arrangement of toes with the #2 and #3 toes pointing forward, and the #1 and #4 toes pointing backward.

The true woodpeckers that I am focusing on in this article actually have just part-time zygodactyl feet. That is, they have versatile feet, and they can alter the direction of some of their toes as needed. The woodpeckers can take the zygodactyl setup when hopping along the ground or perching on a tree limb, but that orientation is not functional when hanging from a tree trunk. In that case they take what is called the ectropodactyl configuration where the #4 toe is rotated to the side, or in some cases forward. See Figure 7 for an illustration of the common ectropodactyl position in a woodpecker.

Figure 6.

Figure 7. Common Woodpecker Ectropodactyl Foot.

Figure 8 shows the less common ectropodactyl configuration which occurs in some woodpeckers that have lost the hallux, and Figure 9 illustrates the Campephilus genus that has an ectropodactyl foot with a long #4 toe pointed upward and with the hallux (#1) pointed to the side.

Figure 8. Ectropodactyl Feet with no Hallux.

Figure 9. Campephilus Ectropodactyl Foot with Hallux to the Side.

Secularists say that all of these woodpeckers have evolved highly effective foot solutions to the specific conditions in which they normally find themselves as they cling to trees and excavate, climb, and peck them. The creationist would say that the woodpeckers have adapted to the conditions as allowed for by their Creator in the beginning. Both would likely agree that the amount and types of morphological foot adaptation that has occurred depends largely on the maximum size of each species.

Woodpecker’s Head: If you are into woodpeckers at all you probably have heard the explanations for how they can peck away at a tree and not get headaches. These explanations all center around the words “shock absorbing.” That is, the woodpecker has been designed (either by God or natural selection depending on the worldview) to have a number of shock-absorbing mechanisms that keep it from harming its brain in a manner like humans do when they get a concussion. Here are some of the suggested mechanisms that have been put forward to solve the supposed problem:

- The beak is made of elastic material.

- The hyoid (muscles and tendons supporting the throat and tongue and reinforcing the head) works to absorb shock.

- There is a spongy bone specially located behind the beak.

- There is a skull bone containing spinal fluid.

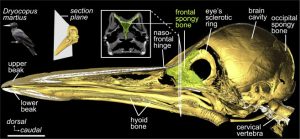

One might think that it would be a good idea to have shock absorbing capability when it is understood that the woodpecker is submitting itself to the following conditions when pecking a tree: the bill strikes at a speed of 20-23 feet (6-7 meters) per second, the resulting deceleration impact force has been measured to be over 600 times the force of gravity (some sources say up to 1,500 times the force of gravity), the strikes are rapid with some woodpeckers having been clocked at 100 to 300 strikes per minute, and many hours of every day may be spent drilling for food or constructing cavities. Figure 10 illustrates the construction of the genus Dryocopus woodpecker skull with its spongy bone in front of its brain cavity.

Figure 10.

For decades numerous studies by engineers and scientists have proposed that the shock absorbing capabilities of the woodpecker could provide a good example for how better helmets could be designed for preventing concussions in humans. In fact, helmets have even been designed taking these assumptions as fact. After all, if nature, using natural selection, has designed the woodpecker in a manner to minimize brain damage, it makes sense that engineers should take advantage of biomimicry in order to design improved concussion-minimizing helmets for people. In the reference list at the end of this article references numbered 1-5 and 9-11 all base some or all of their statements regarding the woodpecker design on its shock absorbing abilities.

Then in 2022 a new engineering study determined that the shock absorption assumption is wrong! In this study high speed photography was used to observe the action of the beak/head assembly when the woodpeckers were actively pecking on wood. The conclusion was that woodpeckers would be poor wood excavators if there really was shock absorption involved in their hammering. They would not want shock absorption any more than a carpenter would want shock absorption in his hammer as he drove nails. The beak tip, the beak, and the skull all move together with no indication of shock absorption as can be seen in the videos taken of several woodpeckers as they peck wood in the Figure 11 video. Be sure to watch the video to better understand the concept.

Figure 11. Woodpecker Pecking Wood Video

The gist of the findings for the shock absorption tests as stated in the abstract for reference #8 follows in the next paragraph. Due to the revolutionary findings of this study, I am sure there will be much more research that will follow.

Abstract: “The hypothesis that the skull of a woodpecker serves as a shock absorber is paradoxical since any absorption or dissipation of the head’s kinetic energy by the skull would likely impair the bird’s hammering performance and is therefore unlikely to have evolved by natural selection. In vivo quantification of impact decelerations during pecking in three woodpecker species and biomechanical models now show that their cranial skeleton is used as a still hammer to enhance pecking performance, and not as a shock-absorbing system to protect the brain.”

Notice the words, “unlikely to have evolved by natural selection” in the above quote. I think it would make more sense (at least from the creationist’s perspective) if it read “unlikely to have been chosen by the engineer of the skeletal system.” Other conclusions of the study indicated that there was no shock absorption designed into the system because it was not needed! The woodpeckers can take the shock in large part due to their size and the design of their skulls.

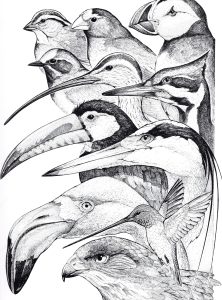

Woodpecker’s Bill: In the true woodpeckers the bill is typically a strong chisel-shaped device that looks designed to do exactly what it needs to do in order to strip bark and excavate holes in trees. Figure 12 illustrates some of the huge differences in the bills of birds that secularists tell us all evolved from an unknown ancestor that evolved from an unknown dinosaur. Consider in Figure 12 the toucan bill (7th from the top) compared to the woodpecker bill (6th from the top) where both birds have been placed in the same phylogenetic order by the evolutionists. There will be more later in this article on the topic of bills when we look at the engineering involved in the tongue of the true woodpecker.

Figure 12. Some Bird-bill Variations.

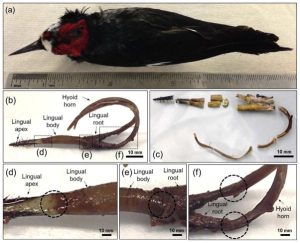

Woodpecker’s Long, Extensible Tongue: Much has been written over the years about the woodpecker’s amazing extensible tongue as illustrated in Figure 13. The tongue actually wraps around the bird’s brain! What I found to be the most interesting aspect of the research on the tongue assembly is the work reported in 2016 by Jung and listed in reference #5 at the end of this article. The essence of their work as described in the abstract was that along with the head, beak and neck, the hyoid apparatus (tongue bone and associated soft tissues) is specifically designed to handle the high impact forces that result from the pecking that the woodpecker does. The authors of this paper conducted structural analyses that determined that this hyoid apparatus is not at all simply constructed but has four distinct bone sections, with three joints between the sections. The sections are engineered to have different impact-absorbing capabilities that all work together to allow for the woodpecker to successfully construct his holes in wood. Figure 14 is one of the illustrations from the Jung paper that shows the organic components of the woodpecker that were structurally analyzed.

Figure 13. Woodpecker Tongue Assembly.

What I conclude from the findings of this kind of research is that the deeper scientists look into the design of living things the more complex are the components found to be, and the less true the random-chance evolutionary explanations for their creation seem. Much of this type of research in biomimicry is done in order to apply the design of living things to human inventions and products. The tragedy is that so much of the engineering discovered in lifeforms is falsely attributed to “Mother Nature” instead of to the Creator God.

Woodpecker’s Nostril Covers: The final engineered feature is that woodpeckers have tuffs of feathers that cover the nostrils to preclude getting wood chips into the breathing system. There are no feathers to act as safety glasses for the eyes as this feature would detract from the bird’s ability to see, but it has been determined that the woodpecker closes its eyes with each impact of its bill in order to prevent construction debris from getting into the eyes.

So far as the fossil evidence shows, woodpeckers have always been woodpeckers. There is no transitional fossil evidence in the rock record showing evolution of woodpeckers from some other kind of bird. In the 4,500 years since the global Flood (that was the cause for the fossils) the six special engineered features have always existed so far as can be determined from the fossils. Of course, there could have been variations and adaptations with the feet, bills and feathers that would not be obvious in fossils, but they would have represented minor changes.

The woodpecker is one of the most amazing of God’s animal creations. Glory be to God!

J.D. Mitchell

References:

1. Backhouse, Frances, Woodpeckers of North America, Firefly Books Ltd., 2005.

2. Bergman, Jerry, “Woodpeckers-Amazing Birds Designed to Peck Wood,” (Chapter 23) in Wonderful & Bizarre Life Forms in Creation, Creation Science Association of Alberta, 2020.

3. Catchpoole, David, “Woodpecker Head-Banging Wonder,” Creation, Vol. 34 No. 3, 2012, p. 43.

4. Gibson, Lorna J., “Woodpecker Pecking: How Woodpeckers Avoid Brain Injury,” Journal of Zoology, 270(3):462-465, 2006.

5. Jung, Jae-Young et al, “Structural Analysis of the Tongue and Hyoid Apparatus in a Woodpecker,” Acta Biomater: 2016 June; 37: 1-13.

6. McKee, Jenny, “New Study Shakes Up Long-held Belief on Woodpecker Hammering,” Audubon Magazine, July 14, 2022.

7. Proctor, Noble S. et al, Manual of Ornithology, Yale University Press, 1993.

8. Van Wassenbergh, Sam et al, “Woodpeckers Minimize Cranial Absorption of Shocks,” Current Biology, 32, 3189-3194, July 24, 2022.

9. Wang, Lizhen et al, “Why Do Woodpeckers Resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical Investigation,” PLOS ONE 6(10): e26490, 2011.

10. Yoon, Sang-Hee et al, “A Mechanical Analysis of Woodpecker Drumming and its Application to Shock-absorbing Systems,” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, Volume 6, Number 1, January 2011.

11. Zoo Guide: A Bible-based Handbook to the Zoo, Answers in Genesis, 2006, pp. 158-59.