On a recent trip to Central Washington, we took a detour to visit the Stonehenge replica at Maryhill. So, I have decided to write about this replica structure in this Part 1 article and also about the original Stonehenge ruins in England in Part 2. Both locations are of great historical interest and with both articles at hand it will be possible to make some fascinating comparisons between the two locations. (I plan to get back to the series of articles about my west coast fossil museum tour next month.)

With both the Part 1 and the Part 2 pieces I will discuss the subject matter similarly providing “what,” “where,” “who,” “when,” and “how” descriptors of each location in that order. First let’s look at the Maryhill, Washington location.

1. What:

The Maryhill Stonehenge replica is part of the Maryhill Museum of Art properties located on a bluff overlooking the Columbia River from the Washington side. The art museum has developed to the point where it has a fairly large collection of art and artifacts that I think is best described as “eclectic.” The art museum is not the subject of this article, however there are many available written as well as online sources for getting the museum history and museum collection information if you are so inclined. One good source is the book referenced in this article.

Maryhill Museum of Art from the east.

Maryhill Museum of Art from the east.

Both the museum and the Stonehenge replica were built by Samuel Hill in the early part of the twentieth century. Hill’s Stonehenge is a conjectural model of the English Stonehenge as Hill envisioned that it might have looked when it was completed. Hill had visited the English ruins in 1915 and incorrectly believed that the ancient monolithic remnants represented a human sacrificial site. As a Quaker he wanted to build a memorial to the local soldiers who had died in what he believed was a worthless and tragic World War I. Hill built his replica as a memorial dedicated specifically to the Klickitat County men who died in the war. Unable to find suitable stone for the replica Hill constructed his replica from reinforced concrete.

Sam Hill’s Stonehenge at Maryhill from the north.

Sam Hill’s Stonehenge at Maryhill from the north.

Sam Hill’s Stonehenge at Maryhill from the south.

Sam Hill’s Stonehenge at Maryhill from the south.

Hill’s Stonehenge interior view.

Hill’s Stonehenge interior view.

Inside on the concrete monoliths are bronze plaques with the names of each individual soldier and a large altar block six feet by 18 feet by three feet high. On the altar block is a large patriotic plaque with what Hill wanted people to remember about the war and the sacrifice each man gave.

Stonehenge individual plaques.

Stonehenge individual plaques.

Large Stonehenge altar rock memorial plaque.

Large Stonehenge altar rock memorial plaque.

The town of Maryhill that Sam Hill founded on 7,000 acres along the Columbia burned down leaving only the museum and the Stonehenge memorial out of his original buildings. Stonehenge is now included on the National Register of Historic Places.

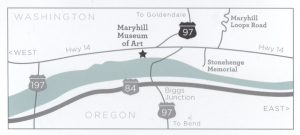

2. Where:

Most people access the art museum and the Stonehenge replica from Interstate 84 on the Oregon side of the Columbia River. The museum is visible from I-84 situated high on the bluff across the river as one approaches the bridge at Biggs Junction. Take the bridge on US highway 97 to the north with the art museum found on Highway 14 to the west and the replica to the east as seen on the map below. The bridge is located about 100 miles east of Portland, Oregon.

The mailing address for the art museum is 35 Maryhill Museum Drive, Goldendale, WA 98620. Admission is free to the memorial, but donations are accepted for ongoing maintenance.

3. Who:

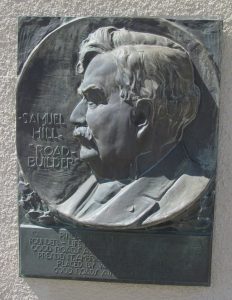

Samuel Hill lived from 1857 to 1931. He has been remembered as a “Visionary. Entrepreneur. World traveler. Road and monument builder. Philanthropist. Friend to royalty.”* He was also known as a Quaker who wanted his town to be populated by an assembly of Quaker farmers. These qualities were offset by his reputation as a womanizer and his propensity to mental depression.

Hill’s family was totally dysfunctional, and he spent his adult life estranged from his wife and two children. To compensate he filled his life with his work and that left a legacy that was very unusual. He was described by many as a man “bigger than life” involved in law, railroads, highway building, and more than fifty trips to Europe. He was a proponent of the Good Roads Movement of the early twentieth century and was the leading face behind better roads for Washington, Oregon, California, and on to South America.

Photo of the ebullient Sam Hill.

Photo of the ebullient Sam Hill.

Hill even experimented with new road-building techniques on his own Maryhill property along the Columbia River. He tried to determine the best ways to provide road drainage and gradients. He searched for the most durable road building materials. Some of his experimental roads still exist below the Maryhill art museum. Hill established the first chair of highway engineering at the University of Washington in 1907. He was even instrumental in the building of the Columbia River Highway in Oregon. There is a long and intriguing story behind Hill’s building of the structure that is now the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Hill’s likeness at the entrance to the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Hill’s likeness at the entrance to the Maryhill Museum of Art.

Sam Hill’s Burial Crypt located below Stonehenge.

Sam Hill’s Burial Crypt located below Stonehenge.

4. When:

a. Maryhill property purchased by Sam Hill: 1908.

b. Sam Hill visited England’s Stonehenge ruins: 1915.

c. Hill’s Stonehenge replica constructed: 1918-1929.

d. Sam Hill passed away: 1931.

e. Maryhill Stonehenge designated as a National Historic Site: 2021.

5. How:

Hill’s Stonehenge is a full-size replica of the original. It has the same number of sarsen stones (30) that encircle the horseshoe of trilithons. The horizontal lintels are basically the same design as those in the original. It could be said that the secondary circle of concrete “stones” approximate the size and location of the bluestones in the original. There is a vertical stone outside that assumes the function of the original Heel Stone in England.

Heel Stone at Maryhill Stonehenge.

Heel Stone at Maryhill Stonehenge.

But, all of Hill’s stones are actually made of steel reinforced concrete. He used crumpled tin on the concrete forms to simulate a hand-hewn look on the surface of his “stones.” Of course, that does not look anything like the actual Stonehenge megalith stones of the English countryside which are in some cases quite smooth. And his straight sided and true vertical stone structures are not like the sides of the originals which are extremely variable so far as verticality and straightness.

There is no mystery regarding how the forms for the concrete structure were made. They were made identically to those used at the Maryhill Museum and the Columbia River Highway projects. An example of the state of the art for reinforced concrete forms can be seen in the photo below. I assume there are actual photos available somewhere of the construction of Hill’s Stonehenge memorial, but I have not been able to find any so far.

Concrete formwork for the Moffett Creek Bridge on the Historic Columbia River Highway.

Concrete formwork for the Moffett Creek Bridge on the Historic Columbia River Highway.

Sam Hill was definitely able to provide for himself a lasting legacy with the Maryhill Museum and the Stonehenge replica. (He also built in 1921 the Peace Portal in Blaine, Washington that is located at the USA-Canada border.) It is not likely his structures and roads will last as long as the megaliths in England, but what he has built on the Columbia River bluff in Washington State should provide amusement and edification to visitors for many generations to come.

J.D. Mitchell

* Maryhill Museum of Art-2nd Edition, Tener and Reynolds, Arcus Publishing, 2017, p. 21.