Galápagos Giant Tortoises are famous due largely to the writings of Charles Darwin and their connection to his theory of evolution through natural selection. Turtles and tortoises are reptiles of the family of vertebrate animals denoted as Testudinidae. This phylogenetic family is recognized especially by the enclosure of the internal body organs in a hard shell, with only the head, neck, limbs, and tail protruding. The term “tortoise” is usually applied only to species in the family that are land-inhabiting types and do not swim. This is article #2 in a four-part series on the topic of the Galápagos Islands and evolution.

The Galápagos Giant Tortoise genus/species designation is Geochelone elephantophus per a majority of experts, although Geochelone nigra is applied by others. This is an example of experts not always agreeing with each other, and in the field of biological taxonomy is a situation that is extremely common. Males are larger than the females and the males can be identified by their longer tails.

These tortoises are called “giant” because they are commonly found to grow from an egg the size of a ping-pong ball to be as much as 500 pounds in weight and up to five feet over the carapace. One study by the Charles Darwin Research Station reported that an Isabela Geochelone sub-species put on 385 pounds in 15 years of observation. No one knows the life span of the Galápagos tortoises, but experts guess that they may live to be 150 years old. Once they gain a substantial size and age they don’t really have to fear any predators except for humans.

Many reports over the centuries document how many thousands of these tortoises were captured and used on ships as food for sailors. The tortoises could be kept alive for long periods since they can live without water or food for extended periods. Their shells and bones would just be chucked overboard at the time of harvesting the meat of each tortoise. These practices resulted in the near extinction of the tortoises until conservation practices were seriously instituted in more recent times. Even today some extant sub-species of the Galápagos tortoises are listed as endangered.

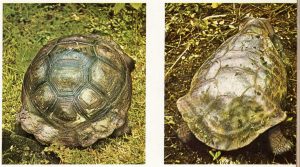

These tortoises have different looking carapaces depending on where they are found in the archipelago. Some of the shells are more rounded or dome shaped. Others are what is described as saddle shaped. Usually the dome-backed tortoises are larger and live on the higher islands where there is more plentiful vegetation that can support their huge size. The lower islands of Pinta, Pinzón, and Espanola are where the smaller saddle-back types are most likely to be found. Within these two basic types up to a dozen sub-species have been identified by specialists. The subspecies have been mostly differentiated by characteristics of their carapace designs. It is often stated by natives that these carapace differences are sufficient to ascertain exactly on which island that a particular tortoise resides. Another general difference between the dome-backed and the saddle-backed tortoises is that the saddle-back types have longer necks and legs than do the dome-backed types. However, all of these tortoises can interbreed and so are clearly of one created kind. There is evidence for variation within that created kind, but there is absolutely no evidence for evolution from one kind to another kind either in living or fossil tortoises.

Dome-shaped and Saddle-shaped Galápagos Tortoise Carapaces

Dome-shaped and Saddle-shaped Galápagos Tortoise Carapaces

The Galápagos Islands are generally thought to have been named after the giant tortoises found there. The Spanish name Insulae de los Galopegos (“Islands of the tortoises”) was assigned to the archipelago on maps at least as early as the 16th century. While the Spanish word tortuga is often used for “turtle/tortoise,” galápago is also a primary translation of the word “tortoise” as well as a descriptor word for a “saddle” (like is used to ride a horse). So, either the archipelago was directly named for the giant tortoises of all descriptions on the islands or it was named specifically for the saddle-shaped carapaces of some of the giant tortoises found there. Your guess is as good as mine.

A fascinating question about the Galápagos tortoises is how did they and the other unique biota get to the islands? There are no history books other than the Bible that can provide us with clues. Evolutionists are really stumped because they believe the islands are millions of years old. With the presupposition that the islands are five million years old then one comes to the conclusion that getting life on the islands would have been a long process.

Here is what God’s Word tells us: Then God said to Noah, “Come out of the ark, you and your wife and you sons and their wives. Bring out every kind of living creature that is with you—the birds, the animals, and all the creatures that move along the ground—so they can multiply on the earth and be fruitful and increase in number on it.” (Genesis 8:15-17)

The first thing we know from this is that the timing of the flora and fauna arrival to the Galápagos had to be after Noah’s Flood about 4,500 years ago not millions of years ago. The archipelago would have been sterile as it was being formed from volcanic eruptions, but we know from the studies of life establishment on Surtsey Island (near Iceland in the twentieth century) that it is a process that takes as little as a few decades not millions of years. Life could after some time, perhaps within less than a thousand years, be well established on the islands. While giant tortoises can float for a while they are not swimmers so there are two likely ways they got to the islands from the mainland. One would be via post-Flood vegetation mats on ocean currents. See the map that shows the present set up for ocean currents in the area.

Ocean Currents That Affect the Galápagos Islands

Ocean Currents That Affect the Galápagos Islands

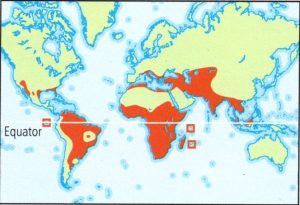

The second possible way for the giant tortoises to get there would be through the actions of humans. Where the Testudinidae family of tortoises now reside is seen in the next map. If we assume that the Galápagos Giant tortoise ancestors came from one of these continental locations, then they could have even been brought from Africa by the Phoenicians. So, I would say they most likely came either by sea on vegetation mats or by the work of human seafarers.

Current Range of Testudinidae Tortoises (Orange Color)

Once a population of tortoises arrived with the minimum number of fertile individuals needed in order to multiply, then the genus/species variation that we now see all over the islands would rather quickly result. In fact secular scientists believe that the saddle-shaped types of Galápagos tortoises have adapted a number of times on the islands as a result of the severe climate changes that are common there. They have also posited that all of the tortoises have come to be from the first ancestors that settled on San Cristobal Island. That is the island that, assuming the present-day ocean currents, would have been the likely first landing place for seafarers.

Evolutionist scientists are amazed by the unbalanced nature of the Galápagos Islands. They are unbalanced in the sense that there are many fauna and flora on the adjacent continents that are not represented on the islands. For example, reptiles are well represented but there are no amphibians, and there are many birds but few mammals. Evolutionists would expect that over millions of years the islands should be more balanced. I think that the fact that in reality the islands are only a few thousand years old might explain this unbalance.

The Galápagos giant tortoises eat only vegetation and even though there are many plant species missing on the islands that they might eat on the mainland, they are able to find there over fifty plant species that they can indeed consume. However, the digestive system of the tortoises is very inefficient. Though they eat large quantities of food when available their digestive system is so inefficient that many of the plants they eat can still be visually identified in their waste. It can take from one to three weeks for food to pass through an individual tortoise.

Nevertheless, these animals are amazing, and God’s engineering is clearly seen in countless ways.

Click here for article #1 in this series on the Galápagos Islands.

J.D. Mitchell

Source List for additional details on the Galápagos Giant Tortoises:

- Cosner, Lita & Sarfati, Jonathan, Creation, “Tortoises of the Galápagos,” Vol. 32 No. 1, August 2010. [Creationist perspective.]

- Darwin, Charles, The Voyage of the Beagle, Chapter XVII, P.F. Collier & Son, 1909. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Fitter, Julian et al, Wildlife of the Galápagos, Princeton University Press, Pocket Guides, 2000. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Horwell, David & Oxford, Pete, Galápagos Wildlife-A Visitor’s Guide, Bradt Publications, 1999. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Jackson, Michael H., Galápagos-A Natural History: Revised & Expanded Edition, University of Calgary Press, 1993. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Mattison, Chris: General Editor, Firefly Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians-Third Edition, Firefly Books, 2015. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Moore, Ruth, Life Nature Library-Evolution, Time, Inc. 1962. [Evolutionist perspective.]

- Purdom, Georgia: General Editor, Galápagos Islands-A Different View, Master Books, 2013. [Creationist perspective.]

- Wieland, Carl, Creation, “Darwin’s Eden,” Vol. 27 No. 3, June-August 2005. [Creationist perspective.]