Lichens are organisms composed of multiple species working together in what is defined as a symbiotic relationship. Unlike plants and animals, lichens do not grow from embryos but develop through the integration of multiple separate organisms. Experts estimate that there are 15,000 to 20,000 species of macro and micro lichens in existence. Macrolichens are common all over the earth and quite visible if you know what you are looking for. Lichens are made up of mostly a primary and sometimes a secondary fungus (80 to 95 percent of the lichen body) and a photosynthesizing partner (5 to 20 percent of the lichen body) which is either algae or cyanobacteria or both. It is estimated that the Pacific Northwest area (where I reside) has about 600 macrolichens species and over 1400 microlichens species that have been identified.

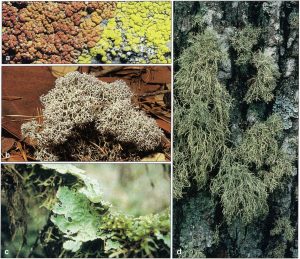

Image of Four Typical Species of Lichen.

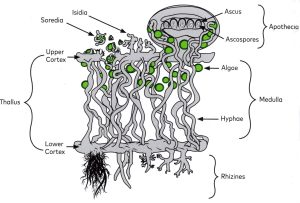

The algae and/or cyanobacteria live inside the body of the fungus body (the thallus) and produce energy through photosynthesis, while other nutrients and minerals are taken directly from the atmosphere and water as it washes over the symbiotic organisms. Lichens do not need soil to live and grow. They are attached to the supporting surface or substrate by what are called rhizines. Rhizines have root-like structures that are formed on the lower lichen surface and attach the lichens to substrates such as soil, wood, bark, rocks, or even concrete. Remember that photosynthesis is the process of using energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars (carbohydrates).

Internal Structures of a Typical Foliose Lichen (McMullin).

The general definition of symbiosis is, “any of several living arrangements between members of two different species, including mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism. Both positive (beneficial) and negative (unfavorable to harmful) associations are therefore included, and the members are called symbionts.” [From https://www.britannica.com/science/lichen.]

When discussing lichens only the positive type of symbiosis (mutualism) is considered.

Lichens are important lifeforms. They are used by humans for medicine and dyes. Indications are that they were once regularly used as food by humans. Lichens provide much of the food supply for caribou and reindeer that live in the far northern hemisphere. They provide camouflage and nesting materials for numerous kinds of animals. They are critical in some areas for helping to stabilize soil against erosion.

Lichens have been categorized into three different structural forms which are crustose, foliose, and fruticose. The crustose has a crust-like lichen growth form that grows tightly to its substrate across the entire lower surface and does not have a visible lower surface. The foliose has a leaf-like growth form, which typically has distinct upper and lower surfaces. The fruticose has a bush-like or hairy form, typically without distinct and lower surfaces. As with all biology, the variations and complexity of lichens become more known with each year of study by the scientists who specialize in them. I am not one of those scientists and so my descriptions in this article certainly are not extensive. I have included some references at the end of this article where more information can be found. After displaying some photos of some lichen that I found in my yard, I will discuss the question of the origin of lichen.

Masses of Lichen Attached to the Branches of a Maple Tree.

Close-up of the Lichen from the Maple Tree.

Lichen on the Trunk of a Large Cherry Tree.

Lichen Attached to the Wood Roof of an Outbuilding.

Lichen Growing on a Concrete Slab.

Lichen Growing with Moss on a Tree Limb.

LICHEN ORIGIN & EVOLUTIONARY THEORY: As a biblical creationist I believe that all plants and animals were created by God according to kinds “very good” in the beginning. It also makes sense that they were designed in the beginning with certain adaptive capabilities that would be needed after the Fall. The question is, were there any mutualistic symbiotic relationships in the beginning like those that exist today with the lichens? Did lichens exist at the time of the creation?

There are creation scientists who have proposed an assumptive answer to the question as follows: “Symbiotic relationships are crucial for the functioning of healthy biospheric processes and ecosystem stability. Philosophical naturalists posit that these relationships evolved, and co-evolved later as natural selection, initially focused on struggle and competition in simple organisms, led to greater complexity and cooperation through system self-organization. Alternatively, God created complex cooperative systems with astounding complexity from the beginning. He initially created organism archetypes programmed for holistic relational interaction, which is an important element in proposed creation-based species concepts. We also interpret extant species interactions in the light of a planet groaning with dysfunction and death. Therefore, we propose a new design model of symbiotic relationships using human-engineered interface systems as viable analogues for understanding and describing them.” [From the abstract of Hennigan et al.]

My take from this paper is that the writers believe that some symbiotic relationships could have existed in the beginning while others came to be after the Fall as a result of the God-designed capabilities of all organisms to adapt to the resulting dysfunction and death caused by man’s sin. The writers rely on human engineering concepts to describe how these symbiotic relationships did and can come to be. The fundamental assumption here is that God’s living designs of symbiosis can best be understood from the application of known engineering (interface) precepts that are discussed in the paper.

My simple presupposition is similar to Hennigan in that I would expect that it is highly possible that some lichen kinds existed at the time of the “very good” creation in order to allow for that creation to be very good. I am not fond of the idea that all lichen could only have come to be after the Fall.

On the other hand, the evolutionist assumption as summarized in the Hennigan abstract is not credible. Here is another statement of the evolutionist assumption by another source: “Mutualistic symbioses have contributed to major transitions in the evolution of life…An emblematic example of mutualism impact on Earth is the transition of plants from the aquatic environment to land, which occurred 450 million years ago and was partly enabled by the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis formed with Glomeromycota fungi. Another emblematic example of a plant-fungi symbiosis occurs in the mutualistic association between certain chlorophyte algae and fungi resulting in the formation of lichens.” [From Puginier et al.]

The online Britannica article on lichens states that: “Evolutionarily, it is not certain when fungi and algae came together to form lichens for the first time, but it was certainly after the mature development of the separate components.”

No matter the level of assumed certainty by evolutionists, the commitment to deep time and the idea of creative random interaction of matter leaves no room for rational thinking. As I have written over and over, natural selection has been shown to have no ability to select whatsoever. Every man-engineered thing ever identified required intelligence. No living thing has ever been seen to come from nothing or advance from one kind of lifeform to another kind of lifeform. The evolutionist assumptions about lichens are total acts of faith in the impossible.

J.D. Mitchell

For more information on lichens and symbiosis:

Hennigan, Guliuzza, & Lansdell, “Interface Systems and Continuous Environmental Tracking as a Design Model for Symbiotic Relationships,” Journal of Creation 36(2) 2022.

Jenkins and Richards, “Symbiosis: Wolf Lichens Harbor a Choir of Fungi,” Current Biology 29, Feb. 4, 2018.

“Lichen,” https://www.britannica.com/science/lichen, accessed March 8, 2024.

Lücking & Spribille, The Lives of Lichens: A Natural History, Princeton University Press, 2024.

Puginier et al, “Phylogenomics Reveals the Evolutionary Origins of Lichenization in Chlorophyte Algae,” Nature Communications (2024) 15:4452.

McMullin, Troy, The Secret World of Lichens: A Young Naturalist’s Guide, Firefly Books, 2022.

Tomkins, Jeffrey, “Symbiotic Lichens Showcase Our Creator’s Ingenuity,” Acts & Facts, vol. 49 no. 2, Feb. 2020, p. 15.